WorldWide Rescue curriculum

W/c 6th September 2021

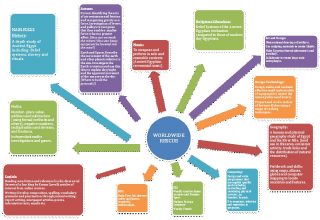

The creation of ‘Worldwide Rescue’ (a global leader in search and rescue operations) begins on day one. We consider the following:

What does a search and rescue team actually DO?

Who might we work on behalf of?

Where do we operate?

What do we need in order to do our job?

The team emerges as pupils are invited to take on the role of team members using dramatic convention. Hearing the backstories of our colleagues, we learn a little about what has motivated them to do such a demanding job. The company logo is designed and chosen, and the equipment store is created.

Monday morning we begin mandatory first aid training. Later on, we return to drama to begin to build our company history by recreating short ‘films’ of instances where our first aid training has been used. The team has conducted searches on mountainsides, in derelict buildings, at sea and deep inside the amazon jungle! We write of some of these experiences.

W/c 13th September 2021

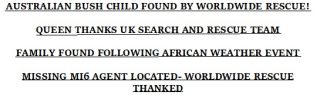

We write online news reports, detailing significant rescues carried out by Worldwide Rescue.

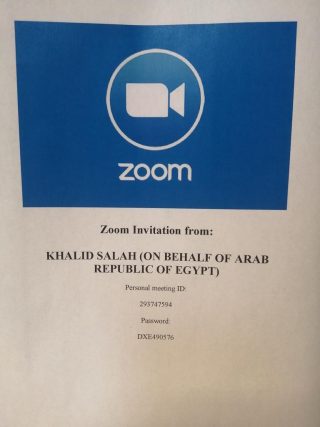

On Monday morning, the company receives a ZOOM meeting invitation:

We are eager to find out what Mr Salah (teacher in role) has to say, and we agree to the meeting. He tells us that some 100km north of Aswan in Egypt, a small, recently opened goldmine has collapsed. He informs us that of the 50 miners working that day only 40 have been located so far. The 10 missing miners are thought to have with them enough supplies for a week, should they be found alive. He warns us that the mine manager, Tarik Hassan, can be something of a difficult character. The team are keen to reassure Mr Salah that they are well equipped to take on this job, and he gives us details of our flight to Luxor.

The team consider the meeting with Mr Salah, and many questions emerge:

Where exactly is the mine? Will we need any specialist equipment? What is it like in Egypt? Why did Mr Salah warn us about Tarik Hassan?

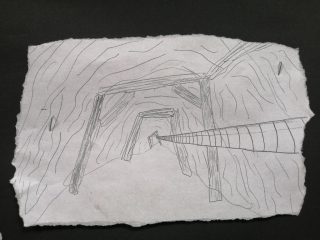

We conduct research into the gold mining process, and the features of different types of mines. Using this information, we co-create a subterranean map of the mine, using appropriate technical language. We sketch various points of interest, and mark the area the missing miners are thought to be located.

This work also leads us to study negative numbers and map work (including scale).

W/c 20th September 2021

Using dramatic convention, we create images. When activated to speak, these still photographs come to life and we assume the role of the gold miners on the fateful day the mine collapsed. We describe how our days started, the work we were doing, and our feelings as we began yet another day underground. Another set of photographs reveal change in mood when we realise something is wrong. We talk of our fears and the questions we ask ourselves the mine collapses around us.

Later, we write of our experiences:

‘There’s a deathly crash, a horrifying bang, and a shrill screech. The rocks crash down on me. I black out.’

‘Deathly screams rattle throughout the silence of the collapsed mine, darkness flows through me.’

‘A large cloud of black dust and breeze, unlike anything I have ever seen before, rushes into my face; something is very wrong’

‘A boulder lands on my leg, I scream and shout, however nobody can hear me. I drastically faint, and my body folds under me.’

Back in role as Worldwide Rescue, we are offered the opportunity to talk to the local volunteers who were first on the scene (through drama), and a debate quickly ensues. Some felt this was unnecessary and that as world leaders in our field that there is nothing to be gained from the phone call. Others felt that as the mine and it’s surroundings are unfamiliar territory, that the phone call is essential. A consensus cannot be reached.

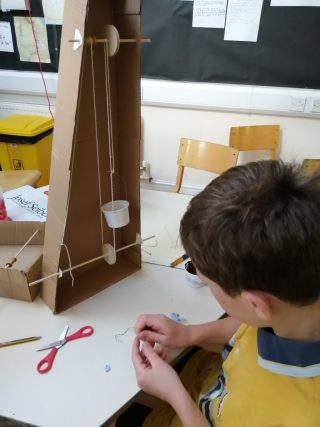

Instead, we attempt to identify some of the potential challenges of the rescue (and search). It is agreed that we will need to clear a great deal of rock in order to conduct the subterranean search. This leads us to investigate forces, and to consider how the use of levers, pulleys, and gears could aid our work. We begin to design possible systems which could be used.

Working with professional choreographer Samantha Moss, pupils are attending weekly creative dance sessions. They are exploring movements and holds based on the idea of rescue, support and trust.

W/c 27th September 2021

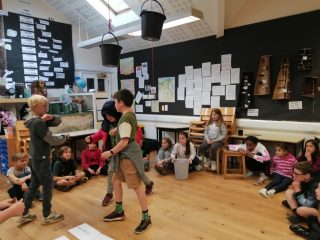

We begin the week by constructing scaled down versions of our pulley designs. The team create a variety of different systems to test including weighted ones, and those comprising of several pulleys. We evaluate our designs and structures, and their impact on forces.

Through drama we create scenes from the airport in Aswan, as the Worldwide Rescue team land in Egypt and are greeted by Khalid Salah (Egyptian Government), Tarik Hassan (Mine Manager), and some of the local volunteer rescue team who conducted the initial search of the collapsed mine.

We note their polite tone of voice and body language, and the relief they clearly feel as we arrive to complete our task. The children are then invited to hear the unspoken layers of thought behind this cordial meeting and are surprised to learn that our actions- or lack of- have preceded us.

We hear of the frustration of Mr Salah and the local SAR team, who are surprised and concerned that Worldwide Rescue have not called ahead to check on conditions at the site. Mr Hassan’s thoughts are also those of concern. We hear of his current arrangement with ‘The Museum’, and that it is an extremely lucrative one. He is inwardly concerned that Worldwide Rescue’s arrival and discovery of whatever it is that he is selling will mean the end of this deal.

Out of role we consider what we have heard. Some are concerned for our safety. Did Tarik Hassan collapse the mine on purpose? What is down there that is so valuable? Are the miners helping him? Is he selling gold ore to the museum, or something else?

We design and write programs that allow us to prepare our remote underground device for use once we reach the collapsed shaft.

W/c 4th October 2021

We look at the yield of the gold mine in the year 2020. We investigate it using formal methods of addition and subtraction, and note the differences between the yield month on month.

We are given the opportunity to observe Tarik Hassan alone in his office. He is composing an email to a Mr Mahmoud. We hear further details of his arrangement with ‘The Museum’. We hear of his fears that the trapped miners will discover his secret, and that this discovery may signal the end of the ‘profitable dealings’ between the two men. Out of role we discuss this and decide that extra caution will be needed as we carry out the rescue

Back in role as Worldwide rescue, we discuss our next steps and agree on our rescue strategies. We consider safety checks, specialist clothing and the preparation and modification of our tools and equipment.

We enter the mineshaft, in role as the team. We voice our thoughts of apprehension, excitement and even fear as the cage descends down the shaft. Some of the team are preoccupied with thoughts of Tarik Hassan, and whether they are currently in danger. We use computer programming to position the robotic device at the top of the chasm under which we believe them miners to located.

Enlisting the skills of a visiting group of teachers from Denmark, we put them into role as the miners. The device allows us to ask them questions. We learn they are not seriously injured, but are cold, scared and hungry. We reassure them and try to offer them words of comfort. They inform us there is little space, but with the one small torch they have they can make out some carvings. They are able to show us these carvings using the robotic device.

A couple of pupils know these carvings to be hieroglyphs, and so we set about deciphering them. The carvings spell out the word ‘AMUN’. Pupils discuss these findings and together we research and decide that the carved rock is likely to be concealing the entrance to an Ancient Egyptian tomb.

We begin to conduct further research and compile reports about Ancient Egyptian tombs, and what might be found in them. We produce a non-chronological report on this. Next week we will create the tomb, and discover some of it’s secrets…

W/c 10th October 2021

We enter the chamber in which Amun is buried. A pupil in role represents the body of Amun, and we hear questions from others as we surround the coffin.

The teacher assumes the role of Amun, and answers some of these questions. Amun was a farmer, who died at age 55 from ‘heart problems’. He tells us of his regret at not being able to save a friend who needed him.

We begin create his tomb, using images based on the information we have gathered during the drama episode and our knowledge of the objects and images which adorned the tombs of Ancient Egyptians.

We carve miniature Shabti dolls to adorn the tomb, and learn that these dolls were to symbolise a ‘workforce’ of servants on behalf of the deceased- so that in the afterlife they would have people to carry out their jobs and tasks!

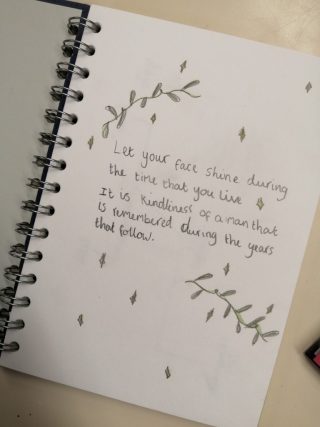

We consider the Ancient Egyptian’s belief in the afterlife, and all that they equipped their tombs with in order to move happily from this life to the next. We write poetry based on this. We write of things we will keep with us as we move forward in life, but also things we will leave behind.

We read about the Ancient Egyptian’s idea of balance and harmony (ma’at), and their love of life and community. Together we create scenes from Amun’s community, and of how people might have kept harmony and balance within it

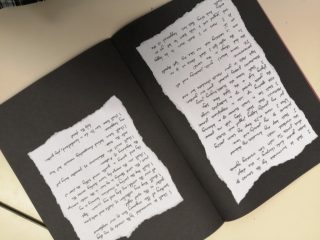

We create Amun’s family tree, and begin what will become his journal in the weeks to come.

W/c 1st November & 8th November 21

A meeting is called by the village elders of Amun’s community. We gather round to hear what they have to say. We take a moment to note the tension in the room, and the concerns we have over what the meeting is going to be about. The elders (teacher and pupil in role) are concerned about the ongoing drought, which is vital to the survival of the community. Without it, crops will not thrive and the farming cycle on which the community relies on will be broken. We pause the meeting and hear the thoughts of those present (pupils in role). We hear deep concern over families’ already diminishing health and welfare, should the floods not come. The community discuss possible solutions to the worsening situation. It is agreed that a community sacrifice will take place.

A pupil in role comforts her crying baby. He is always hungry as food is becoming scarce.

A pupil in role comforts her crying baby. He is always hungry as food is becoming scarce.

Others at the meeting tell us they have had to resort to begging for food and water.

Others at the meeting tell us they have had to resort to begging for food and water.

This drama episode leads us to study physical and human geography. We examine how vital the annual rains were to farmers who lived close to the River Nile, and how the rains affected the settlements along its banks. We use found objects to create soundscapes of Amun’s community by the Nile River, noting the different features of the pieces such as texture, pulse, timbre and pitch etc. In addition, we write some powerful accounts of the tension fuelled meeting in our journals.

We co-create the sacrifice, with each of us in role as a member of the community laying down a treasured or valuable item in the hope of pleasing the Gods Stobek and Hapi, so that they might bring the rains. More journal entries are written, and we learn more about the Ancient Egyptian Gods.

Back in our narrative, time is moved forwards by a few weeks. We overhear conversations between members of Amun’s family (pupils in role), which are becoming ever fraught as the drought continues. We hear of that his children- Isis and Iago- wish to run away to seek food and water for their family. We hear Amun and his brother Adjo discussing plans to relocate the family. We also hear a conversation between them where Adjo (teacher in role) shares with Amun a rumour he has heard: The Pharaoh is scouting for new bodyguards…

W/c 15th November 2021

In role as Amun and his family, we arrive at the steps of the temple in Thebes. There we are met be two men (pupil and teacher in-role). They reveal themselves to be the commander-in-chief of the military and the vizier to the young King Tut. Their names are Horremheb and Ay.

They confirm that new bodyguards for the Pharaoh are indeed needed. They speak for the young King and explain to the crowd, (including Amun and his family), what the work will entail. It is revealed that there are opportunities for children to train as scribes. There is a buzz of excitement in the crowd; these opportunities would transform lives and take the struggling farming families away from potential poverty and starvation!

Out of role, however. Pupils are quick to voice their suspicions about the two men. They question their manner and responses to some questions asked by the crowd. They sense that the two men are dismissive of any direct questions about the young Pharaoh. In the out of role discussions that follow, pupils conject whether the two men might be using their position of trust to meet their own needs and desires.

Employing the use of another dramatic convention, a pupil represents the Pharaoh. As we activate him to speak, each of us are invited to voice his thoughts as we consider what it must have been like to be a young leader at 18 years old.

Out of role, more journal entries are created. In addition, we write a persuasive ‘speech’ to deliver to the Pharaoh and his advisors, which details exactly why he should consider Amun for the position of bodyguard. We research the role of scribes in Ancient Egypt, and their importance in society. We also consider what a ‘respectful relationship’ is, in light of the potential manipulation of King Tut by his elders. We examine how one might reach out, and who to, should they ever feel they are being used or manipulated. We create Egyptian jewelry and costumes.

W/c 22 & 29 November 2021

With Amun having been accepted into the Pharaoh’s household as a bodyguard and his children as scribes, we return to dramatic convention to explore the relationship between Amun and his master- King Tut.

Children assume and move between these roles as we create moments between the Pharaoh and his new bodyguard. In role as Amun, some pupils seek to befriend and reassure the young leader. Others are keen to discuss with their master about Horemheb and Ay, and to express their concern about on-going manipulation. Other pupils take the role of the young Pharaoh seek to confide in Amun for advice. It becomes clear that a solid, trustful friendship between the pair has formed.

Pupils overhear a conversation between Horemheb and Ay (teachers in role), where they are discussing arrangements for the building of the Pharoah’s Tomb. Out of role they question why a tomb might be under construction when the Pharoah was of such a young age. We learn that although the construction of the Tomb of a Pharaoh would certainly begin prior to their death, this might also have been due to the leader’s poor health and the anticipation of an early death.

Later, we are to observe a Priest (teacher in role) marking out the tomb, carefully observing the sky and miming the use of an instrument- an image of which lays beside the scene.

Immediately questions emerge:

What is the instrument? How does it work? Why would it be used? Is the Priest measuring the sky? Why?

We read about Ancient Egyptian astronomy, and how temples and tombs would be built to align with celestial bodies. We also read that a Merkhet could be used to measure and track the alignment of the stars and the time at night, as well as a surveying device. Out of role we take the opportunity to learn about the Earth’s rotation and the movement of the planets within the Solar System relative to the Sun.

W/c 6 December 2021

Pupils enter the room to find the body of Tutankhamun (symbolically represented on paper). The Pharoah is dead. Pupils are invited to assume the role of Amun once again and to share their elegiac reflections at his passing. Later, we write of them in our journals.

“I will live in grief at not being able to save you” Billy

I was your bodyguard; I should have protected you” Eliza

“Your short life was a great one my friend, go now peacefully to the afterlife” Jacob

We theorise how the death might have occurred.

Through dramatic convention we create scenes during the preparations for mummification. Out of role we are able to write a set of instructions on ‘How to mummify a body’. We also do some hands-on mummification- with tomatoes! They are safely buried in the Key Stage 2 garden, ready to be exhumed in a few months.

Pupils decide they wish to leave our drama narrative by creating ‘photographs’ of Amun’s remaining years- before he died at age 57 and was buried in a tomb in Aswan (which would later be discovered by the trapped gold miners and Worldwide Rescue).

We see him living out his days back by the Nile River as a farmer (once the rains had returned)- just as he was when we created him all those weeks ago.